I was flown to Kauai Island for a business trip in the summer of 2016. My main objective was to explore and document the popular beaches both above and underwater, in order to create a nice reference page for anyone traveling to the island for a vacation. (I hope you it serves you well; we worked really hard to ensure the information ended up clear, accurate, and beautiful!) Kauai has one main road that wraps around almost three-quarters of the island. As I canvassed the beaches throughout my trip – at times revisiting the same ones while waiting for safe snorkeling conditions and good visibility underwater – I frequently drove past a sign pointing the way to the Kilauea Lighthouse.

Soon, I had just a few days left on island. I was traveling north toward the Na Pali Coast for my first order of business, and I again passed the Kilauea Lighthouse sign. I realized that even though the site wasn’t on my to-do list, I had time to stop and take a few shots for our social media. I’m so glad I made that choice, because the time I spent there turned out to be much more exciting than I’d expected.

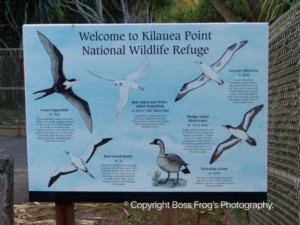

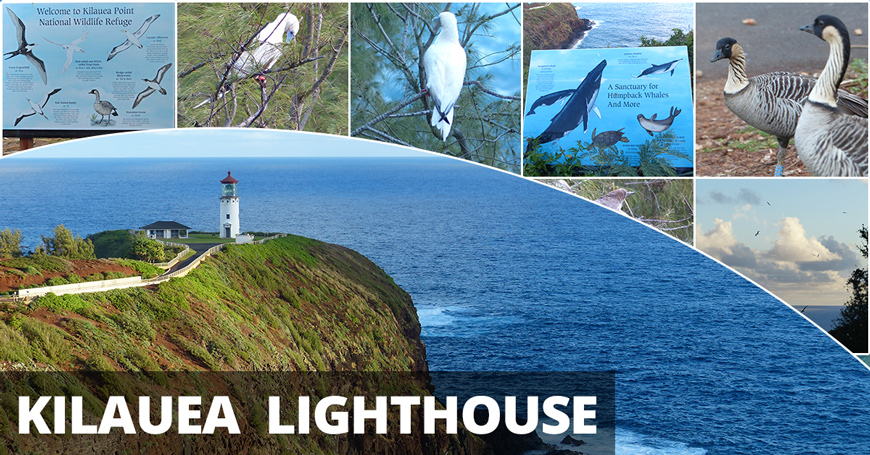

The whole place was full of seabirds! Hundreds of red-footed boobies swooped and dived from the crags in the cliffs, riding the air currents above the water. When I looked out to sea past the top of the lighthouse, I could see the distinctive, seemingly lazy float of great frigatebirds! Below the flying birds, the water in the cove was smashing up against the rocks, with a layer of whitewater constantly regenerating along the surface.

When I had first gotten out of the car, it was about 6:30 in the morning, and hardly any people were there. If you are a birdwatcher like I am, you know how imperative it is to get up early to watch birds interact, and also to have the best chance to run into them in the first place. Midday, birds may be around, but they are generally a lot more restful than they are in the mornings or at dusk. When it comes to this spot on Kauai though, you’re likely to see a few representative nene geese in the parking lot no matter what time you arrive.

I walked slowly up to the fence separating me from semi-certain death by distracted plunge to the rocks below. I was scanning the sky, and I could have easily kept walking. When I’m in the presence of birds, I’ll often zone out. As I’m sure you’re aware, we humans tend to do that when we see something we’re crazy about. Isn’t it great?

I was having an amazing morning, but I felt a bit envious of the birds. I mean, how often have you wanted to sprout wings and fly free of a situation? (That’s what vacations are for, I suppose.) Lucky for us, we have the ability to fly over to Kauai on a plane, which is quite a bit easier than powering a pair of wings with our arms and back. Over the centuries, human-powered bird wings have been proven to be an impossibility, but not for lack of trying: the attempts have been magnificent!

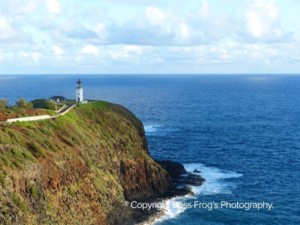

As I watched the birds execute their expert flight patterns, the Kilauea Lighthouse itself was standing tall atop Kilauea Point. Relative to where I stood, the 52-foot-tall structure was left-of-center. The sun was not yet over the horizon, but the effects of its impending rise touched everything, and the glass globe of the lighthouse began to shine with an outer glow.

One visitor’s face lit up with a smile as he pointed out a red-footed booby chick swaying on a branch. The chick was working on balancing and preening himself at the same time. Watching him spread his wings to keep himself upright, I was impressed with his dedication to learning his craft. I did notice that he didn’t have any down feathers, and he was the same size as adults, but his greyish-brown plumage was a completely different color than the bulk of boobies present. I too assumed he was a chick, because all the boobies that I could see flying sported mostly white feathers with some black accents. When I looked up the chick’s coloration later on, I found out he was actually an adult. I learned that adult red-footed boobies exist in all sorts of color morphs, and all the colors breed in the same areas – the cliffs around Kilauea Lighthouse being one of them.

Another cool thing was the fact that these birds have webbed feet, and I saw them grasping onto branches just like birds without webbed feet. I hadn’t realized that webbed-footed birds could do that! Once I saw it happening, I decided that I must have been thinking about real-life birds from a cartoon-watcher’s perspective. I mean, Daffy Duck never perches, he just walks around with his feet splayed out, right? And now, I’m pretty sure I’m dating myself.

When the Kilauea Lighthouse was operational – from 1913 to 1975, it guided ships traveling between Hawaii and Asia with a beam of light that shone across 22 miles of ocean! The huge lens floated on 260 pounds/118 kilograms of mercury. (This silvery, liquid, transition metal – symbolized by Hg on the periodic table – has since been found to be toxic to our health.) As you might suppose, the powerful beacon was turned off each morning – when the actual sun came on duty. If you ever get into trouble for not turning off the lights when you leave a room, think of what the implications would be if you were a lighthouse keeper!

After the Kilauea Lighthouse went dark for the last time, the building fell prey to the same effects that all beachfront properties face: damage from constant salt, wind, sun, and humidity. Luckily, U.S. Senator Daniel K. Inouye, who served Hawaii in Congress for 49 years, spent time and energy raising funds to restore the historic structure.

In 2013, the lighthouse was made beautiful again! It was not switched on, because the lens would again have needed mercury for support. At that point (Kilauea Point? If I’m writing right, that should elicit a groan from many of you), the lighthouse was joyfully christened the Daniel K. Inouye Kilauea Point Lighthouse.

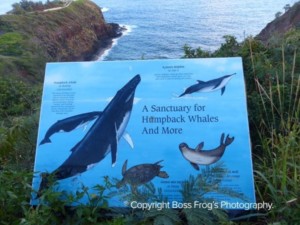

Back to the birds – personally my favorite part of seeing the Kilauea Lighthouse, I recently attended one of Maui Ocean Center aquarium’s monthly lectures. Speaker Emily Severson of the Maui Nui Seabird Recovery Project explained the effects of man-made lights at night on seabirds and newly hatched sea turtles. It turns out that lights of the wrong intensity and/or direction impede these animals’ ability to find their way to the ocean, to live.

Some seabird species go to sea to hunt at night. When they confuse a land-based light for the moon they naturally follow, they will circle it – searching desperately for the water – until they exhaust themselves and drop from the sky, often to their deaths. Sea turtle hatchlings use moonlight on the water to lead them to their waves, too, and bright shore-based lights can turn them in the wrong direction. When this misdirection occurs, the baby turtles struggle forward on their tiny flippers until their strength gives out completely or they run into a predator. Plus, lights on the coast can discourage adult female turtles from nesting on the beach in the first place.

The soaring upside of this environmental issue is that once we understand all the connections – and we do, we can successfully solve it. You may have noticed that many of Hawaii’s coastal roads are unlit, some resorts use dimmer, down-facing lighting, and owners of shoreline condos often ask you to keep their outside lights off at night. Now you can see – and marine life can sea! – why.

I asked Emily if the beams from lighthouses ever disturbed seabirds. She told me that lighthouse beams are sometimes confused as avian navigational aids, but not as frequently now that their fixed lights have been replaced with rotating ones.

You can visit the lighthouse itself (rather than simply seeing it from afar, as I did) Tuesday through Saturday from 10:00 am – 4:00 pm. If you’d like more information than the link above provides, you can send a message to the coolest e-mail address ever, as far as I’m concerned: ShineOnKilauea@yahoo.com.

Aloha for now, and shine on, my friends! Shine on. . .